One aspect of Akka Streams newcomers often have difficulty to grok is the one of materialized values. This concept comes up even in the simplest of examples and is often glossed over without a satisfactory explanation. This creates an aura of mystery which mislead people into deeming it far more complex than what it actually is.

I’ve witnessed developers being on their toes regarding materialized values even after becoming comfortable with some of Akka Streams’ undeniably more complex features.

In this article I’m gonna try to give an in-depth coverage of all there is to know about materialized values using as a guide the questions and doubts I had while learning the library:

- why are they needed?

- how do they compose?

- how can we return our own values?

Why are they needed? 🔗

The short answer to this question is that materialized values give us a communication channel with the various stages of our stream.

In the case of a hello world example, this channel is used to inform us of the completion of the stream.

val done: Future[Done] = Source.repeat("Hello world")

.take(3)

.runWith(Sink.foreach(println))

The same pattern applies when we want to access the value computed by a stream.

val result: Future[Int] = Source(1 to 10)

.runWith(Sink.fold(0)(_ + _))

This however is only one (even if prevalent) use of these communication channels.

Another, slightly more complicated, use of materialization value could arise when we have an unbounded source (for example producing messages read from a Kafka topic) and we want to perform a graceful shutdown. This requires sending a command to the source instructing it to stop polling for new data and complete it.

val stream: RunnableGraph[Control, Future[Done]] = Consumer

.plainSource(consumerSettings, Subscriptions.topic("my-topic")

.toMat(Sink.foreach(println))(Keep.both)

val (control, done) = stream.run()

// … when we want to shutdown

control.shutdown()

Ok, so we need a way for the stream to communicate with the outside world, but is it really necessary to introduce this complexity? Couldn’t we achieve the same result by simply using closures to provide the stream feedback channel and the control interface?

Let’s try to implement this strategy for the feedback channel.

val promise = Promise[Done]()

val stream: RunnableGraph[NotUsed] = Source.repeat("Hello world")

.take(3)

.to {

Sink.foreach(println).mapMaterializedValue { done =>

done.onComplete {

case Success(_) => promise.success(Done)

case Failure(ex) => promise.fail(ex)

}

}

val streamDone: Future[Done] = promise.future

Everything seems to work as expected! We achieved the same outcome without relying on the value generated as a result of running the stream.

However what would happen if we were to wait for the streamDone future to complete and then run the stream a second time?

Well in this case we would have a failure trying to complete the promise: once a promise has been completed it cannot change its value, thus every attempt at doing so by calling success or fail on it raises an exception. Even worse, if we were to try and use the promise to get another future to wait for the second run termination, we would get back an already completed future with the result of the first run, effectively making it impossible to receive any signal from the second run.

This experiment allows us to conclude that materialized values are necessary to enable stream stages to be reused multiple times. By having stages create their communication channel only when the stream is run Akka Streams ensures that different stream instantiations are independent.

How do they compose? 🔗

Now that we understand why materialized values are needed let’s try and shed some light on how they work.

First of all, it is important to note that materialized values are not some special properties of sinks and sources. Indeed every stage in Akka Streams needs to produce a value during the materialization phase (i.e. when the stream is executed). In case a stage doesn’t have anything meaningful to produce it is the convention to use the singleton type NotUsed.

When we want to connect 2 independently defined stages we incur a problem: the result of this composition will be itself a stage that needs to declare the type it will produce during the materialization. But given that we are just connecting 2 already define stages, which of the 2 materialized values should we adopt?

We might think that a sensible solution is to just collect all of them into a list and let the user decide how to handle it. This approach however has a pretty evident disadvantage: given that each stage can materialize a value of any type, the resulting list would need to be a List[Any]. We might be tempted to try and exploit tuples to regain our types (by adding a lot of specialized operators for all the possible arities of the stages, or by relying on a library like Shapeless) however we soon realize that this would become unmanageable as the number of stages in our pipeline increases.

So we reach the conclusion that the better strategy is to deal with materialized values while combining stages. This indeed is the same conclusion Akka’s authors have come up with.

To this end Akka Streams offers us 2 operators viaMat and toMat which require us to provide a combination function used to produce the materialization value of the composition of the stages. Most of the time what we are interested in is just to select one of the two stages' values or possibly to grab them both. This is so common that the library provides an implementation of these strategies:

Keep.left: select the materialization value of the left (upstream) stageKeep.right: select the materialization value of the right (downstream) stageKeep.both: collet both materialization values into a tuple

To further improve developer convenience and code readability Akka Streams provides a variation of the above operators which automatically apply the Keep.left combination function: via and to.

A concrete example 🔗

In order to fix into our mind all the things we’ve said so far let’s try and play with a simple example.

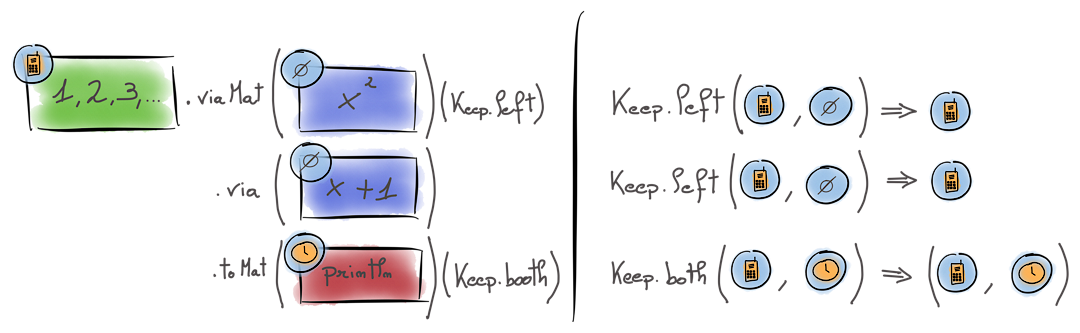

We want to build a simple stream that given a source of integers, computes their square, increments the result by one, and finally prints them to video. The catch is that we want to be able to control when the source should stop emitting new elements from outside the stream. To do this we have our source materialize a ControlInterface. To properly wait for all elements to be processed before terminating the program, we need also need to have our sink materialize a Future[Done].

Now that we understand how materialized values composes we can use the operators we discussed in the previous section to get a tuple containing both the ControlInterface and the Future[Done].

trait ControlInterface {

def stop(): Unit

}

val source: Source[Int, ControlInterface] = ???

val flow1: Flow[Int, Int, NotUsed] = Flow[Int].map(x => x * x)

val flow2: Flow[Int, Int, NotUsed] = Flow[Int].map(x => x + 1)

val sink: Sink[Int, Future[Done]] = Sink.foreach(println)

val (control, doneF): (ControlInterface, Future[Done]) = source

.viaMat(flow1)(Keep.left) // explicitly specifying Keep.left

.via(flow2) // implicitly specifying Keep.left

.toMat(sink)(Keep.both) // collecting both values

.run()

system.scheduler.scheduleOnce(2.seconds) {

println("Stopping the source")

control.stop()

}

doneF.onComplete { result =>

result match {

case Success(_) =>

println("The stream completed successfully")

case Failure(ex) =>

println(s"The stream failed with exception: ${ex}")

}

system.terminate()

}

The following diagram illustrates how the various combination functions are chained to obtain our final result.

How can we return our own values? 🔗

At this point, we feel comfortable working with materialized values and we are able to use the various combinator functions to guide the materialization into producing exactly the data we are interested in.

However, there is still something that bothers us: what if we wanted to have a stage that produces a materialized value of our choosing? The last example featured a source returning a type we defined: ControlInterface. This cannot be something that a built-in stage can have generated.

Indeed Akka Streams still has some tricks up its sleeve to work on materialized values. Up until this point we’ve only really handled them via the composition functions we specify when combining 2 stages. As we have seen these functions take 2 values and return a new value as a result. In all the examples we’ve seen so far this result was only a projection, however we could have opted to return an entirely different type. In the last example instead of returning a tuple of the ControlInterface and the Future[Done] we could have opted to create a case class MyMaterializedValue containing them.

This intuition should make us wonder if something similar is possible also when operating on a single stage. That is indeed the case: we can use the method mapMaterializeValue to apply a transformation to the materialized value of a source, flow, or sink. This method takes as an argument a function that given the current value needs to produce a new value.

Let’s see how we can use this feature to implement the source from the last example:

class ControlInterfaceImpl(killSwitch: KillSwitch)

extends ControlInterface {

def stop(): Unit = killSwitch.shutdown()

}

val source: Source[Int, ControlInterface] =

Source.fromIterator(() => Iterator.from(1))

.throttle(1, 500.millis)

.viaMat(KillSwitches.single)(Keep.right)

.mapMaterializedValue(s => new ControlInterfaceImpl(s))

The idea is to leverage a kill switch stage to interrupt the generation of new integers and wrap the materialized KillSwitch instance into an implementation of our ControlInterface.

This strategy of handling materialized values is a good approach when we want to repackage the current value into something else. This helps in avoiding leaking too many details of how our stages are implemented leaving room to tweak the internal representation without breaking source compatibility.

An important observation we can make on this scheme is that inside the mapMaterializedValue we are free to close over whatever value without any chance for Akka Streams to tell us if we are doing something potentially dangerous. As we already discussed in previous sections, stages once defined can be materialized multiple times. Thus we must be extra careful not to close over values that are not intended to be used multiple times (remember the example on promises).

This strategy covers the majority of situations where we need to operate on materialized values, so we could stop here. However in the preface I stated that this article would be an in-depth coverage of the topic, so let’s go on. In the remainder of this section, we will see how to create a custom stage that materializes a value of our choosing.

So let’s imagine that for some reason we find ourselves unable or unwilling to use kill switches as a mechanism to implement the ControlInterface. We need an alternative way to communicate with our source to signal we want it to stop producing new values.

To achieve this we will use the GraphStage API: this is the lowest level API of Akka Streams used to build all of the base stages. Explaining this API alone could be the topic of a full article, so we are not going to dwell on the details of how it works. Instead, we will limit ourselves to discuss the parts which are functional to working with materialized values.

Given that our main objective is to produce a materialized value we will use a variant of the API called GraphStageWithMaterializedValue which allows us to define a factory that creates both the logic and the value of our stage.

The idea behind our implementation will be rather simple: we’ll define a stage of shape Source which will produce integers starting from a specified number and provide a callback function which we will use to complete the stage when invoked.

class AsyncCallbackControlInterface(callback: AsyncCallback[Unit])

extends ControlInterface {

def stop(): Unit = {

callback.invoke( () )

}

}

class StoppableIntSource(from: Int)

extends GraphStageWithMaterializedValue[

SourceShape[Int],

ControlInterface

] {

val out: Outlet[Int] = Outlet("out")

def shape: SourceShape[Int] = SourceShape(out)

class StoppableIntSourceLogic(_shape: Shape)

extends GraphStageLogic(shape) {

private[StoppableIntSource] val stopCallback: AsyncCallback[Unit] = {

getAsyncCallback[Unit](

(_) =>

completeStage()

)

}

private var next: Int = from

setHandler(out, new OutHandler {

def onPull(): Unit = {

push(out, next)

next += 1

}

})

}

def createLogicAndMaterializedValue(inheritedAttributes: Attributes)

: (GraphStageLogic, ControlInterface) = {

val logic = new StoppableIntSourceLogic(shape)

val controlInterface =

new AsyncCallbackControlInterface(logic.stopCallback)

logic -> controlInterface

}

}

Most of the code is rather simple if a little verbose. The only important bit is the one regarding the handling of the stopCallback. For starters, we can see that we defined a dedicated class for the stage logic instead of defining it anonymously as it is usually done when working with GraphStage. This is so that can have access to the callback from the outside of the class. Indeed looking at the createLogicAndMaterializedValue method we can see that first we create the logic and then we extract the callback and wrap it inside our ControlInterface implementation.

The other thing to note is that inside the AsyncCallbackControlInterface we are not calling the callback directly but instead we are using the invoke method. This will schedule the execution of our callback code asynchronously by interleaving it with the data handling logic of our stage. This strategy guarantees us that while the callback code is executing, no other thread will have access to the GraphStageLogic instance, so we are safe to operate on its mutable state or perform management operations.

We can now use our StoppableIntSource to implement the source:

val source: Source[Int, ControlInterface] =

Source.fromGraph(new StoppableIntSource(1))

.throttle(1, 500.millis)

At this point, we should have a good understanding of materialized values and how to handle them. We might think that the functionalities we have covered are enough to implement whatever program we might think of. However, Akka Streams still has an ace up its sleeve which comes to our help when we face particularly tricky situations.

Let’s talk pre-materialization 🔗

Let’s suppose we need to perform some streaming computations on integers similarly to how we’ve done in the previous examples, however much more complex. Luckily we found a library that seems to do exactly what we need and exposes a simple API we can use!

trait AmazingLibrary {

def complexComputation(source: Source[Int, _]): Future[Int]

}

We can just plug our source in, grab the result, and be done early with our day. Right?

Thinking about the beer that awaits us as soon as we finish this last task, we start piecing things together until we realize that the library is handling the materialization of the stream by itself.

This means that we will not be able to obtain a reference to our ControlInterface, which means that the stream will never terminate which in turn will result in the future returned by the library to never complete. We can see our pint of beer vanishing before our eyes.

However, Akka Streams comes to our rescue with another trick: pre-materialization.

The problem we are facing is that we’ve lost control of the materialization of the stream, however if we were able to materialize just our source and grab its materialized value we would be fine. Prematerialization allows us to do just that.

When a stage is pre-materialized Akka instantiates it and gives us its materialized value while at the same time creating a linked stage which we can then pass around. This linked stage can then be materialized as many times as we want just like normal stages, however it remains linked to the original stage we have pre-materialized. This means that, if for any reason, the pre-materialized stage completes, all future materialization of the linked stage will result in a stream that immediately completes.

Let’s see how we can use the pre-materialization feature to plug our source into this amazing library.

val source: Source[Int, ControlInterface] =

Source.fromGraph(new StoppableIntSource(1))

.throttle(1, 500.millis)

val (control: ControlInterface, linkedSource: Source[Int, NotUsed]) =

source.preMaterialize()

val amazingLibrary: AmazingLibrary = ???

val resutlF: Future[Int] =

amazingLibrary.complexComputation(linkedSource)

Akka Streams provides a preMaterialize operator for both Source and Sink however, at least as of version 2.6.17, it doesn’t feature one for Flow. It is indeed much rarer to be in a situation where this functionality is needed for flows, however it does happen. There is an Akka issue proposing its addition with a snippet implementation that you can use in your project right now while waiting for Akka to include the functionality natively.

Conclusion 🔗

In this article, we’ve introduced materialized values, explain the reason why they exist, and seen various examples showing how to use them. The aim was to provide an holistic coverage of the topic in order to give the reader a better feel for the subject.

There’s no substitute for playing with the library and trying to understand how the various concepts interact with each other to build a deep understanding, but hopefully this piece can serve as a guideline to better focus your exploration.